A problem in today’s world of automobiles is how to fairly compare the efficiency of vehicles with differing types of engines and fuels. One solution is Miles per Gallon Energy Equivalent (MPGe), used by the X Prize for their automotive competition and by the EPA to rate electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids. MPGe is a useful standard: for example, it brought the Nissan Leaf’s initial claim of 367 MPG down to a more realistic 99 MPGe.

MPGe compares the energy content of various fuels to that contained in a gallon of gasoline: approximately 115,400 BTUs, as shown in the following table:

BTU FUEL QTY UNIT

115,400 Gasoline 1.000 US Gallon

115,400 E85 1.414 US Gallon

115,400 Diesel 0.899 US Gallon

115,400 Electricity 33.7 kWh

Edison2 chose to run our X Prize cars on E85 for technical reasons, and because of the MPGe metric there was no penalty for the fuel’s inherently low energy content, just as there was no advantage for someone running a higher energy content fuel like diesel. It’s the energy content of the fuel compared with a gallon of gas that’s at stake, not the volume.

The bottom line is that a gallon of gas has the same energy content as about 1.4 gallons of E85 or 0.9 gallons of diesel. How far you go on this quantity of any of these fuels is your MPGe figure. Here’s how this works out:

FUEL MPGe MPG Gallons / 100 miles

Gasoline 100 100 1.000

E85 100 70.7 1.414

Diesel 100 111.2 0.899

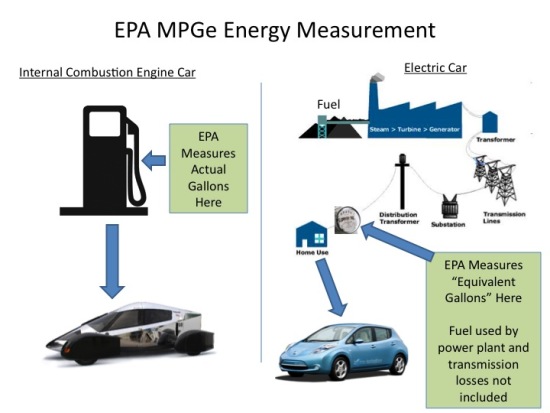

With electricity the process is similar. Fully charge the battery pack, run the car, and measure with a calibrated meter the electricity needed to fully recharge. This method – “plug to wheels” – was used by the X Prize and is used by the EPA.

But some people, including those of us at Edison2, see a problem with the “plug to wheels” metric: it fails to take into account generation and transmission losses associated with electricity. For example, in 2004 6.4% of the electricity generated in the US was “lost” in transmission and distribution (this figure is higher in many countries, such as 15.8% in Mexico), and half or more of the energy generated at a coal-powered electric plant is lost as heat. Thermal conversion in an internal combustion engine, of course, occurs under the hood, but a plug-to-wheels accounting for EVs does not consider energy generation.

But there are metrics that look at the bigger picture of efficiency and measure vehicles “well to wheels”. Argonne National Lab’s GREET model (Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions and Energy use in Transportation) looks at the upstream efficiency of fuel sources – such as transmission and generation losses – and was used by the X Prize in calculating emissions. Likewise the CAFE standards for emissions will gradually factor in the upstream emissions.

But these issues with MPGe are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to confusing or even misleading claims for MPG, due in part to the differences world-wide in assessing efficiency. As an example, VW made headlines this year with their 313 MPG diesel plug-in hybrid XL1 concept. However, this admittedly very efficient two-seater is rated using imperial gallons, which are 25% larger than US gallons, on the European NEDC testing cycle, which does not take into account the energy stored in the car’s 5 kWh battery. Considering these factors, and the higher energy content of diesel, the XL1 gets in the neighborhood of 106 MPGe (but because NEDC is a different drive cycle than the stricter EPA cycle an accurate comparison is really not possible).

MPGe may not be perfect, but it is a good and reasonably fair place to start in comparing automobile efficiency. Adding in upstream energy losses – for all fuels – would make it even better.