Our prototype electric Very Light Car (eVLC) was recently in an EPA-accredited lab for the full gamut of certified economy and range tests. Often this kind of thing is shrouded in secrecy but we thought it might be interesting to publish and discuss the actual results sheet (click here for a pdf).

Starting in the top left corner, we have Roush Industries’ logo. Jack Roush is well known as a successful NASCAR team owner and at the time of writing one of his drivers, Carl Edwards, is leading the Sprint Cup series standings. Less well known is that Roush has facilities all over the Detroit area providing engineering and testing services for the auto industry. We have enjoyed working with the professionals at their emissions lab in Livonia, MI.

The first block of data under the logo names the car tested, in this case VLC chassis #004, and, because it’s critical to the validity of the results, the tire pressure used. 44 psi is Continental’s recommended pressure for the DOT approved tires we use on the VLC.

The next block of information is the dyno settings. Because of its battery, the eVLC is heavier than our E85 powered cars, weighing 1140 pounds and, since the EPA standard is to add 200lb for the driver, Roush set the dyno for 1340 pounds. The car’s drag and rolling resistance characteristics are defined by 3 numbers determined by an SAE standard coastdown test. We’ve written extensively about this before and our numbers are A=6.31, B=0.1862 and C=0.00433. There’s a procedure to match the dyno to the coastdown ABC numbers and the compensating numbers are on the right. Once they’re set, the dyno provides exactly the same resistance to motion and acceleration as the real car on a straight and level road on a windless day.

Is “straight and level on a windless day” the same as “real world”? While you don’t have to deal with wind and corners in the lab, straight and level does prevent people measuring energy consumption coming down the mountain and ignoring what it would take to go back up. In any event it is the EPA standard and what everyone adheres to.

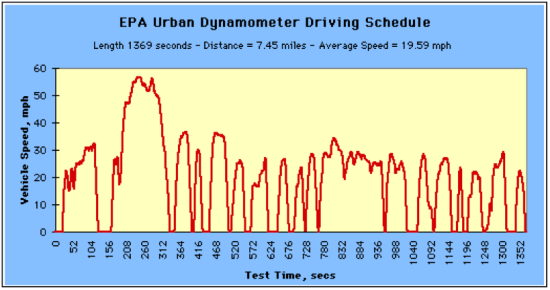

The CARB All Electric Urban Range test consists of running successive EPA Urban Dynamometer Driving Schedules (UDDS) with a 10-minute soak after each completed cycle. This continues until the car can no longer maintain the required speed trace or until the test is called off. The UDDS cycle, which can be found in 40 CFR, Part 86, Appendix I, is shown below.

Edison2’s Ron Cerven drove the test. Although Roush didn’t record the car’s odometer reading, that is not significant because the dyno has a very accurate odometer built in, and it shows that we went 114.781 miles on a charge.

A word about driving the test. The speed profile from the graphic above is presented as a rolling strip chart and the driver has to keep the car’s speed on the target line. There’s a permitted error band but it’s tight and you have to concentrate hard to stay in the acceptable range. If you go outside the error band for more than a few seconds, in a test lasting several hours, you fail. Our being issued a results sheet shows Ron drove the test within the specs.

Charging the battery must begin within 1 hour of the range test finish and the electricity used is measured and recorded. There’s a brutally simple way of making sure this is an honest full charge: you have to do the Highway range test the following day on the electricity you put in.

Roush measured 11.0 kWh of electricity, and the EPA says 1 gallon of gas is 33.705 kWh, so the Equivalent Fuel Economy is 114.781 * (33.705/11.0) = 351.7 mpg.

Note the DC energy used figure of 8.5 kWh. This is measured at the car’s electric motor and the 22.7% reduction is due to losses in the charger, the battery and the controller. If you were to cherry pick and use 8.5 kWh in the calculations, the miles per energy gallon would be higher but the EPA very properly insists the number of record is what goes into the charger.

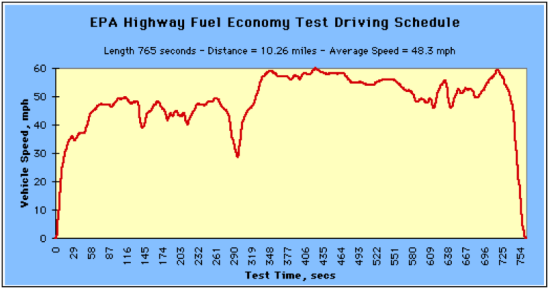

The same test procedure is used on the highway range test, using the EPA’s Highway Fuel Economy Test (HWFET) cycle. This is run repeatedly with a 10 minute soak between each pass until the vehicle can no longer maintain the drive schedule or the test is called off. Once again, battery recharging must start within an hour of the test’s completion. The electricity used to recharge is measured and recorded. The eVLC went 113.331 miles on 11.0 kWh for 347.3 mpg equivalent fuel economy.

EPA procedure is to determine range by averaging Urban and Highway mileage, weighted 55% Urban, 45% Highway and rounded to the nearest 10. Our 114.1 mile combined range therefore got rounded down to the 110 mile official number for Calculated Driving Range.

Further down on the sheet, the last two rows on the sheet involve the EPA’s recently introduced 5-cycle standard. Time was, a new car’s “sticker” mileage was determined solely by the 55/45 combination of the UDDS Urban and HWFET Highway cycles. Since 2008 has been determined by calculated values according to EPA formulae which factor in cold weather (meaning the heater’s on), hot weather (meaning lots of a/c use) and aggressive driving.

At the bottom is the number that really matters: MPG with 30% Cap (Combined) of 244.8 is the eVLC’s “sticker” energy mileage according to the current EPA methodology. It directly compares with the Leaf’s official 99 mpg and the Volt’s 93 when running on its battery. To restate this in different words, Edison2’s eVLC scores 245% and 261% of Nissan’s and Chevy’s energy mileage.

The EPA also applies their 5 cycle formulae to determine the official value for range. In our case, they calculate 79.9 miles. The corresponding Leaf number is 72.5 miles on a battery almost 2 ½ times the size.

Lastly, although the X PRIZE wound up more than a year ago, we thought it would be interesting to see what we would have scored with an electric VLC so we ran the X PRIZE test which consists of 4 successive UDDS + HWFET drive cycles with a 10 minute gap between each one. The whole test was a touch over 71 miles and we used 7.0 kWh of electricity to do it. That electricity is equivalent to 0.208 gallons of gasoline so, the way the X Prize would measure it, we did 71/0.208 = 341.8 MPGe.

341.8 MPGe is an interesting number because we’ve demonstrated 104 MPGe in the same tests with our E85 ethanol/gasoline blend powered cars. When the cars are very similar and the tests are the same, why the factor of 3+ difference? The answer is the motor of an electric car is greatly more efficient than even the best combustion engine. Against that, the electricity measurement is plug-to-wheels and ignores the upstream inefficiencies (generation and transmission losses) of the electricity supply chain.

Regardless, at Edison2 we’re energy source agnostic. Our efficiency is in the car, and whatever you run the car on, you just don’t need as much of it.